![]()

MICHEL FOUCAULT : LE GIP, L’HISTOIRE ET L’ACTION

![]()

![]()

Thèse soutenue en philosophie sous la direction de Monsieur François Delaporte en novembre 2006 à l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne d’Amiens (80) – Mention « Très honorable et félicitations du jury.

Composition du jury :

René Schérer, Professeur émérite de Philosophie, Université de Paris 8,

Alain Brossat, Professeur de Philosophie, Université de Paris 8,

Patrice Pinell, Professeur de Sociologie, IRESCO, Paris,

Olivier Forcade, Professeur d’Histoire Contemporaine, Université de Picardie, Amiens,

François Delaporte, Professeur de Philosophie, Université de Picardie, Amiens.

![]()

RÉSUMÉ :

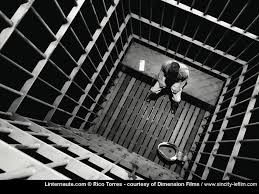

Le premier texte de Michel Foucault sur la prison est un texte militant : il s’agit du Manifeste annonçant, le 8 février 1971, la création d’un Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons. L’objectif de ce collectif est de donner la parole aux prisonniers de droit commun. En 1975, Foucault publie Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison. L’objectif de ce livre est de construire une « généalogie de l’actuel complexe scientifico-judiciaire ». À sa lecture, nous sommes surpris de voir une telle prégnance de l’actualité : il est impossible d’oublier l’expérience du GIP. Quelles relations peut-on établir entre ces deux investigations ? Quels liens cette histoire de la prison et l’actualité des problèmes liés au système carcéral entretiennent-elles ?

Dans cette thèse, nous montrons que ce diagnostic porté sur les prisons et leur histoire relève d’une résistance « par logique ». Il exprime également un acte de courage qui, face au pouvoir de normalisation et d’individualisation « descendante », devient un art de l’ « inservitude volontaire ». Autrement dit : les actions de Foucault au sein du GIP, comme ses recherches historico-philosophiques sur la pénalité, participent de cet êthos selon lequel « contredire est un devoir ».

![]()

SOMMAIRE :

MICHEL FOUCAULT : LE GIP, L’HISTOIRE ET L’ACTION

PREFACE de René Schérer : « combat contre l’intolérable »

CHAPITRE 1 : État des lieux des années 50-60.

1° La réforme Amor

2° Débats

3° Mutineries

CHAPITRE 2 : Le Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons.

1° Le GIP, Groupe d’Information sur les Prisons

2° Les mutineries de l’hiver 1971-1972

3° Le GIP, de fait, modifie son action

CHAPITRE 3 : Surveiller et punir.

1° Une pratique historico-philosophique

2°Polémiques

3° Une généalogie du pouvoir disciplinaire

CHAPITRE 4 : L’histoire et l’action.

1° Un nouveau rapport entre la théorie et la pratique

2° Le présent et l’actualité

3° « Contredire est un devoir »

![]()

![]()

En espérant que cette thèse, faite avec rigueur et conviction, serve à d’autres ;

En espérant qu’elle puisse intéresser des étudiants, des chercheurs, des praticiens ou tout autre public ;

En espérant simplement aussi faire connaître ce sujet passionnant…

![]()

Aussi, je voudrais ici remercier René Schérer, ce chercheur et militant sans compromis, pour sa magnifique et généreuse préface. Avec toute mon admiration et toute ma reconnaissance, encore merci.

Enfin, je voudrais à ce propos vous conseiller la lecture de ses ouvrages et particulièrement ceux, bien sûr, dont la réflexion porte sur l’hospitalité ; l’HOSPITALITÉ dont l’éloge est aujourd’hui nécessaire .

Je vous invite donc en premier lieu à lire Hospitalités aux éditions Anthropos, publié en 2004. Ce livre rassemble plusieurs textes consacrés à ce thème par René Schérer depuis 1993, depuis la parution de Zeus hospitalier.

![]()

![]()

![]()

L’hospitalité consiste essentiellement dans le rapport à l’autre qu’elle introduit. Recevoir, accueillir, reconnaître en l’autre son semblable et, de plus, apprécier sa présence, son contact, comme un apport et un enrichissement, non comme une gêne fait passer du plan d’une conception qui valorise « le même », l’identité au détriment de tout ce qui est étranger, au plan d’une philosophie qui attache une plus grande valeur à l’autre, au respect des différences. Il y a, aujourd’hui, très souvent combat entre ces deux attitudes d’esprit, et il est clair qu’un problème social, un « cas » ne sera pas abordé de même manière si l’on adopte pour traiter l’une ou l’autre attitude : celle qui tend à limiter l’accès à l’étranger, y voyant un intrus, un parasite, et celle qui voit en sa présence une source d’enrichissement collectif.

![]()

15 mars 2010 at 14:59

[…] A., Michel Foucault, le GIP, l’histoire et l’action, Tgèse de philosophie soutenue en 2006, https://detentions.wordpress.com/michel-foucault-le-gip-lhistoire-et-laction/ Lameyre Xavier et Salas Denis (Dir.), Prisons. Permanence d’un débat, La Documentation […]

16 mars 2010 at 14:33

[…] Kiefer A. , Michel Foucault, le GIP, l’histoire et l’action, Tgèse de philosophie soutenue en 2006, https://detentions.wordpress.com/michel-foucault-le-gip-lhistoire-et-laction/ […]

16 août 2012 at 6:30

Très inspirant! Chapeau!

23 juillet 2013 at 21:19

When I wrote « The Battle Roar of Silence – Foucault and The Carceral System » I wanted to share my reading of Foucault’s analysis of power, discourse, and knowledge from a genealogical and archaeological perspective. Foucault actually states that he never wrote for ‘readers’ but for ‘users’, and I certainly used his works! This reading focused on law, punishment, democracy and the contemporary political culture.The basic thrust of this reading is that today ‘power’ has monopolised and is mainly concerned with reproducing the interests of an elite associated with a ruthless neo liberalism. The discourse that is manufactured today, particularly through knowledge and the academia, is atomised and appears as discourse fractals. In splendid isolation these are often unrecognisable. However, the propositions this discourse disseminates are the very basis of a logic structure that consumers of this discourse draw upon to relate and understand reality. These very discourse fractals actually build « plausibility-structures » and allow these consumers to then assemble their own individual syllogisms and logic. This re-enforces a value belief system in which individuals believe they are exercising a form of ‘rationality’ that is objective, scientific and true, while also giving the impression of autonomy and freedom. The carceral system at certain junctures and certain instances appears to be the R & D of this mode of production of discourse, particularly through the pseudo-scientific discourse it creates. However, incarceration may also unveil and demystify these forms of alienation by illustrating the despotism of these orders, and the fragility of ‘freedom’ as espoused by law, punishment and democracy. This reveals the possibility of « radical freedom ». The process itself accrues an amount of frustrations that despotic order creates, that are suffered in silence. This accumulated silence, becomes the battle roar of silence, as Foucault alerted.

Having read most of Michel Foucault’s works, this book, though primarily about the carceral system, was not singularly influenced by his ‘Discipline and Punish – The Birth of the Penitentiary’. The book is influenced by Foucault’s general system of archaeological and genealogical investigation of discourse, knowledge and power, explicated forcefully and provocatively throughout his works. This investigation was actually conceived in several stages, both readings related to Foucault, as well as the other topics covered in my text. It was the result of systematic reading concerned with the despotism of power, and the flaws of democracy. It was a text moved by the rapid erosion of human rights and justice. This is a political text.

My readings of Foucault were undertaken in an order that was different to the chronological order Foucault wrote his texts. The main Foucault texts I read were written by Foucault in the following chronological order: ‘Madness and Civilisation’, ‘The Birth of the Clinic’, ‘The Order of Things’, ‘The Archaeology of Knowledge’, ‘Discipline and Punish’, and the three volumes of ‘The History of Sexuality’. I started off reading his ‘Discipline and Punish’, followed by ‘Madness and Civilisation’, the three volumes of ‘The History of Sexuality’, ‘The, Archaeology of Knowledge’, ‘The Order of Things’, and finally, ‘The Birth of the Clinic’, also reading some other texts of his at some point during this reading. The point of this chronological presentation is simply that Foucault’s thought was constantly evolving, and he was regularly revising his own thoughts, as even the changes in various editions of his work illustrate. Thus the order I undertook, quite unintentionally, allowed me to note aspects of this evolution, and the relevance of this change. Having read the above-cited major works, I then ventured to read a number of other French thinkers that either influenced Foucault (like Althusser, Bachelard, Canguilhem, and Derrida among others), as well as those that were influenced by Foucault (like Badiou, Deleuze, Guattari, and Lyotard). Some years later, I read a number of Foucault ‘readers’ by authors like Gutting, Oliver, and, one of my favourite ‘readings’ (for it corroborated my interpretation and reading), Deleuze.

Another part of my investigation concerned the philosophy of punishment, including readings on morality, ethics, justice, law, human rights, and carceral systems. Here my search, incidentally via comments Said made about Bachelard, and Derrida about ‘the wisdom of the prison cell’, also explored ‘space’ readings. This led to readings on psychoanalysis, particularly the works of Freud, Fromm, and Marcuse, and the relationships between psychoanalysis and mind. Other subjects like neurology, institutionalisation, cybernetics, media imagery, organised crime dynamics, and political culture were also useful. The relationships of these knowledge-clusters to the carceral system discourse and globalisation illustrated that the spirit of ‘democracy’ was rapidly being eroded by despotic legal systems built upon the very carceral system discourse. Citizens in various jurisdictions were suffering in silence the consequences of these despotic systems sustained primarily by deception.

‘The Battle Roar of Silence – Foucault and The Carceral System’ actually shows how these despotic forces operate to deny political literacy, consciousness, and the exercise of fundamental human rights. The importance of this book is that it actually highlights the deficiencies and ruthlessness of neo liberalism, and the limits of freedom it imposes. This book shows how freedom is gradually being ‘circled-in’ by ‘governmentality’, that actually structures the plausibility of its logic and discourse through the carceral system. This text is a politically-charged critique of a subtle ideology that has felt comfortable enough to raise its ugly head safe in the knowledge it can despotically oppress simply because the discourse it has created via institutions like the carceral system, can be circulated to recruit consent and constrain contestation, while consumers of this discourse suffer in silence. The accumulated suffering of these citizens has now become ‘The Battle Roar of Silence’. People all over the world are close to reaching their ‘tipping-point’, and many of those who have realised they will only be saved by themselves, have in fact translated their ‘silence’ into a ‘battle roar’ of affirmative action of revolt. These citizens now take to street to battle against vicious riot squads and power hungry despots. Reading ‘The Battle Roar of Silence – Foucault and The Carceral System’ allows readers to understand these complex dynamics. Its also liberates citizens from the constraints of despotic dominance.

All this work was undertaken in a prison cell while I served more than a decade of incarceration. I was fortunate to also have been visited by various academics who taught at the prison school. During these years I also read works by other major thinkers like Marx, the Frankfurt School, Kant, Hume, Bourdieu, Mao, Dostoevesky, Badiou, Gramsci, al-Koni, Baudrillard, Ibn Taymiyya, Ritzer, Freire, and many others. Naturally, I admit the prison environment was conducive to critical reflection. This work was the actual ‘work-in-progress’ that led to my very own perspective transformation and development.

5 mars 2014 at 17:29

[…] contre la volonté populaire. Pour ma part, je pense que c’est la seconde. Ce qui rendait le combat de Michel Foucault pour les droits des prisonniers admirable, c’est qu’il avait pour but de s’assurer que les principes de […]